Cleanup crews have gone home and emergency food supplies have ended, yet indigenous communities affected by two oil spills early this year remain on edge.

- The 40-year-old Northern Peruvian Pipeline has spilled oil into remote rivers three times so far in 2016.

- Mongabay visited sites affected by two spills that occurred this winter and found oil-coated fields and residents concerned about the safety of the crops and river fish they depend on.

- Advocates are pushing for more studies into long-term health effects from the oil contamination.

- Meanwhile, the Peruvian government has sanctioned the state-owned company responsible for the pipeline and fired its president.

Por Kevin Floerke and Rebecca Wolff

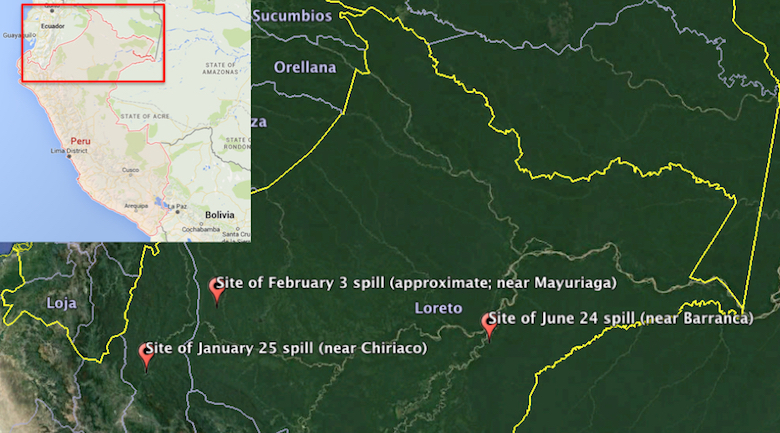

On June 24, reports surfaced that once again the Northern Peruvian Pipeline was leaking oil into Peru’s Marañon River. It was the pipeline’s third major spill this year, after one on January 25 along the Chiriaco River in the region of Amazonas (called the Chiriaco spill) and another on February 3 near the Morona River in the region of Loreto (called the Morona spill). The 40-year-old pipeline has suffered at least 20 spills in the past 5 years alone.

The pipeline, which snakes over 530 miles across the country, belongs to Petroperú, Peru’s state-sponsored oil company. The company’s cleanup efforts for the three recent spills have focused on mitigating the long-term environmental impacts of the oil. But the repercussions for the 8,000-plus mostly indigenous people affected by the spills, whose livelihoods depend on the rivers and land, appear likely to linger.

The government and Petroperú have delivered clean water, cooking oil, and rice to affected communities, but advocacy groups complain that the response has been insufficient. And while Petroperú and local branches of the Ministry of Health conducted basic health assessments and offered emergency health services, community members and indigenous rights advocates report that health providers arrived almost a month after the Chiriaco and Morona spills and that services were not offered to the majority of communities affected.

Advocates contend that the neglect is part of a larger problem in which indigenous communities are often left devastated and unsupported in the wake of environmental disasters, their recovery slowed by systemic inequality.

In late May, before the latest spill, Mongabay visited the area affected by the January 25 Chiriaco spill as Petroperú was finishing a massive cleanup procedure near the town of Chiriaco. Of this year’s three spills, this one was the biggest. Three thousand barrels of crude oil flowed into the Chiriaco River, and from there into the Marañon River, a tributary of the Amazon. It affected some 3,900 residents in at least 22 communities, according to the Institute of Legal Defense (IDL), a Peruvian advocacy group that has taken up the communities’ cause.

Clear water

Huarcaya said the cleanup was conducted according to a rigorous set of international protocols designed to ensure that the long-term environmental effects of the disaster are minimal.

The base camp included a medical office where spill-site workers, including many locals, were checked for symptoms of oil contamination upon ending their contracts with the company. Signs posted outside the main office, written in both Spanish and the indigenous language of Awajún, strictly forbade the employment of minors. These were likely a reaction to accusations of exploitative and dangerous practices leveled shortly after the spill, including that Petroperú paid children to clean up oil without protective gear.

Huarcaya categorically denied those reports. “We have followed strict procedures and have had clear oversight. I have children of my own, I would never allow that,” he said.

At the time of Mongabay’s visit, Huarcaya was finalizing the cleanup operation. “We are in our final stages, the cleanup is complete and we only have to finish some reforestation and compliance checks. If all goes well we will be home in fifteen days,” he said.

A short walk to the Chiriaco River nearby seemed to confirm Huarcaya’s optimism. By all accounts in the weeks following the spill the Chiriaco ran black with a slick and pungent layer of crude. Now, clear water ran under a concrete bridge.

However, a trip downriver to the banks of the nearby Marañon River cast doubt on the sunny prognosis of Petroperú’s engineers.

Food insecurity

Temashnum is an Awajún indigenous community of roughly 500 residents on the banks of the Marañon. It is one of 20 indigenous communities identified to be at risk from the Chiriaco spill, according to IDL.

The Awajún and the Wampis are two of the major indigenous groups affected by the spills in Amazonas and Loreto. Both groups grow the majority of their staple crops on river beaches, and they depend on the rivers for drinking water and fishing.

But the beaches in many communities were inundated with oil when the pipeline burst.

One of them was where Levita, a Temashnum resident who requested that her full name not be used to protect her family’s privacy, grew her yucca. She told Mongabay that the food provided by Petroperú in the wake of the disaster soon ran out.

“I ate food from my field after the spill,” Levita said. “Nobody told us it was dangerous, and I had nothing else to feed my children.”

The struggle to find sufficient food and water in the wake of the spills is a major concern for communities and indigenous rights advocates. In the town of Barranca, near the site of the most recent oil spill on June 24, the Peruvian government has declared a water sanitation emergency and committed to providing 90 days worth of drinking water to affected residents. Petroperú provided kits of water and food. It remains unclear whether these provisions will be enough. The spill affected 750 people, according to a July 12 report from the National Civil Defense Institute, a government agency.

Liseth Atamain, head of the indigenous organization Cultura Awajun, worked closely with Awajún communities affected by the January 25 Chiriaco spill. Emergency rations provided by the Peruvian government and Petroperú were simply not enough, and the Awajún continue to suffer from food insecurity, she told Mongabay.

“Our major protein source is fish from the river, but now they are contaminated. As well, production for the sale and consumption of cassava, plantain, peanuts, cacao, and other food has suffered, they are totally covered in oil,” she said. “It is a serious food crisis.”

According to a report prepared by the local Association of Food Producers, land belonging to more than 300 independent farmers was contaminated in Temashnum and two neighboring communities alone. Jusoe Esash Unum, the association’s president, told Mongabay that although Petroperú cleaned the contaminated rivers, the company refused to clean smaller farm plots or fields, arguing that it would be too expensive.

“We cannot safely plant on this land for the next three years. This means that the farmers who depend upon those plots will not have food to feed their families, or money to buy school supplies for their children,” Unum said.

Unum calculated that the contamination would result in a loss of two million Peruvian soles ($600,000) annually. “Some families have told me they will continue to eat the food from the contaminated fields. They say they have no other option. They ask me, ‘What else are we supposed to eat?’ We tell them they are endangering their health, but all they can say is ‘If I die it is my own fault,’” he said.

In Temashnum, Levita scraped off the top layer of dirt in her field to reveal a one-inch-thick layer of caked black tar. “They never came to clean this area. The oil is still on the ground, and we don’t know if it is safe to plant or not,” she said.

Mongabay showed photos of fields in Temashnum that remained covered in oil to a top engineering official at Petroperú’s base camp. “How can we even establish that is our oil?” replied the official, who asked not to be identified in order to avoid backlash from the company for participating in the interview.

When asked about the possibility of follow-up consultations or a return to finish the cleaning, he said “If we returned to clean tomorrow, the next day we would have twenty other communities here claiming the cleanup wasn’t finished. They would dump barrels of oil on their own fields to receive more work. Do you know how much we are paying them? Too much.”

Near the site of the February 3 Morona spill, Wampis communities are unsure whether fish, a key part of their diet, are still contaminated with oil. Studies conducted there since the spill by the National Agency for Fisheries Health (SANIPES) found cadmium in fish used for human consumption, as well as cadmium and lead in fish from the Chiriaco site. An April SANIPES report on the studies concluded that the harmful heavy metals were “due to the impact that the ecosystem has suffered from the oil spills” and recommended continuing a restriction on consumption of food from the rivers. However, IDL maintains that these results were never communicated directly to affected communities.

Back in Temashnum, Eliseo Akuts, secretary to the community’s president, lamented, “Nobody has come to study our river, nobody has looked at the fish. How can we know if it is safe to eat? How can we feel as though the government cares about us?”

Despite the calls for additional support, on May 27 the regional government of Amazonas declared that the Chiriaco spill “no longer merits emergency relief” and announced an end to its humanitarian assistance.

Health concerns

Advocacy groups have sprung into action to address communities’ complaints.

Ismael Vega Diaz is the director of the Amazonian Center for Anthropology and Practical Application (CAAAP), an advocacy group working to provide legal and political assistance to Amazonian communities. During a conversation in his Lima office Diaz told Mongabay that the actions taken by Petroperú in wake of the spills are insufficient. “They do not have contingency plans that guarantee sufficient reactions to this kind of disaster, so the problems facing these communities will persist,” he said.

After the spills in Chiriaco and Morona the Peruvian government conducted and released a variety of reports on water quality and immediate health impacts on people, in addition to those on heavy metals in fish. However, the frequency and extent of such studies is a point of contention for indigenous advocates and organizations. IDL reported that while the General Directorate of Environmental Health (DIGESA) studied water quality after the spill three times in Chiriaco and twice in Morona, the agency’s effort did not fulfill a supreme court decree mandating daily monitoring after a spill until water is entirely safe to drink again.

In interviews with Mongabay, employees of both CAAAP and IDL expressed concern that study results and recommendations were not easily accessible to communities, and that further investigation into the long-term consequences of the spills on soil, food, and health was lacking. As an example, they pointed to the fact that it took two years for the Ministry of Health to complete and release a study on health effects in residents recovering from a devastating 2014 spill on the same pipeline in the village of Cuninico in Loreto. It found that about two-thirds of adult participants had higher than normal levels of cadmium and the neurotoxic heavy metal mercury in their urine, although it was not designed to determine the source of the exposure.

Using that study as a model, CAAAP and other advocacy organizations are carrying out an independent health assessment focused on the community of Nazareth near the Chiriaco spill site, where many children reportedly assisted in the cleanup. The study will include analysis of children’s blood and urine to determine whether they show any signs of long-term contamination.

Richard O’Diana, a CAAAP lawyer, told Mongabay he hopes the Nazareth study will force the Ministry of Health to support victims of the 2016 spills by demonstrating that they, too, could have serious long-term health effects. He said the study could lead to legal action questioning the ministry’s lack of investigation into the health repercussions of the recent spills in Amazonas and Loreto.

Two months after the Chiriaco spill the regional government of Amazonas published a report noting that over 450 people had sought medical attention for symptoms related to oil contamination. But without further studies, it remains unclear how many people may still be suffering health effects from the spills.

Levita, for one, still is. She worked for Petroperú during the cleanup. Two weeks before the end of her employment period she said she began to feel ill. “I went to see [Petroperú’s] doctor, but they didn’t even examine me. They asked me some questions about how I felt and told me it was just a flu. They said I would get better soon. They gave me a shot for the pain, but they didn’t give me any more medicine,” she said.

She told Mongabay she had been sick for the several months since. “At its worst, I thought I was going to die. The headaches were so strong it felt like my eyes were going to fall out of my head,” she said. She picked up her two-year-old son and wiped his nose, which was red with irritation. “He has been sick since the spill too, but thank God his symptoms are not as bad as mine.”

When asked whether her former employer had provided any follow-up medical care Levita simply shook her head. “Petroperú has not come back to check on me. They say I have a flu, why would they check on me?”

Pressure on Petroperú

Juan Carlos Ruíz Molleda is a lawyer with IDL who has been pressuring the Peruvian government to fine Petroperú over the 2014 Cuninico spill and the three 2016 spills.

“[Cuninico] was the first time anyone has been able to establish culpability on the part of Petroperú or any extractive industry for an oil spill and its subsequent effect on public health,” Molleda told Mongabay.

In each of the previous oil spills along its Northern Peruvian Pipeline, Petroperú had claimed that sabotage by indigenous activists was the cause. But with the Cuninico spill, Molleda and IDL finally established that the spills on the aging pipeline were due to a lack of maintenance and the sole responsibility of Petroperú.

The most recent oil spill on June 24 near Barranca occurred after Petroperú continued to pump oil on the pipeline despite having been ordered to cease operations until it had repaired the pipeline by the Agency for Environmental Assessment and Enforcement (OEFA), the government body that monitors environmental effects of extractive industries.

CAAAP and IDL now hope they can prove that persistent health problems in communities affected by the recent spills are a direct result of environmental oil contamination. If they succeed, Molleda said the case for Petroperú to compensate individuals affected by the spills is strong. “The legal framework exists in Peru, following several years of decisions, that now we can press for direct compensation,” he said.

Despite Petroperú’s close ties with the Peruvian state, pressure on Petroperú is at an all time high. On June 24 OEFA sanctioned Petroperú over it’s failed cleanup of the 2014 spill in Cuninico, and the agency has three other cases open against the company related to the 2016 Chiriaco and Moreno spills that could result in millions of dollars in fines. OEFA’s most recent sanction against the company, on June 30, resulted in the resignation of Petroperú’s president Germán Velazquez as well as a fine of 11 million soles ($3.35 million)for last month’s spill in Barranca and “repeated and systemic violation of their environmental obligations.”

Communities in limbo

Legal proceedings, while important to future relations between extractive industries and indigenous communities, often take years to resolve. Meanwhile, people living in Temashnum and elsewhere remain unable to sell their agricultural products or obtain meaningful medical consultations.

“Every day I wake up and hope the pain is not too bad for me to work. Every day I try to find a way to feed my children.” Levita said. “We are all still alive, and we hope we will remain healthy and not get worse. It is difficult, the way we have been ignored. It feels as though the government does not care about us. It feels like we have been forgotten.”

At his home in Temashnum, Akuts sat at his kitchen table and stole a glance at his infant son. “We want to be sure that in the future our people are treated with respect, and that those responsible for these disasters are held responsible. We only want what is right, justice for our people.”